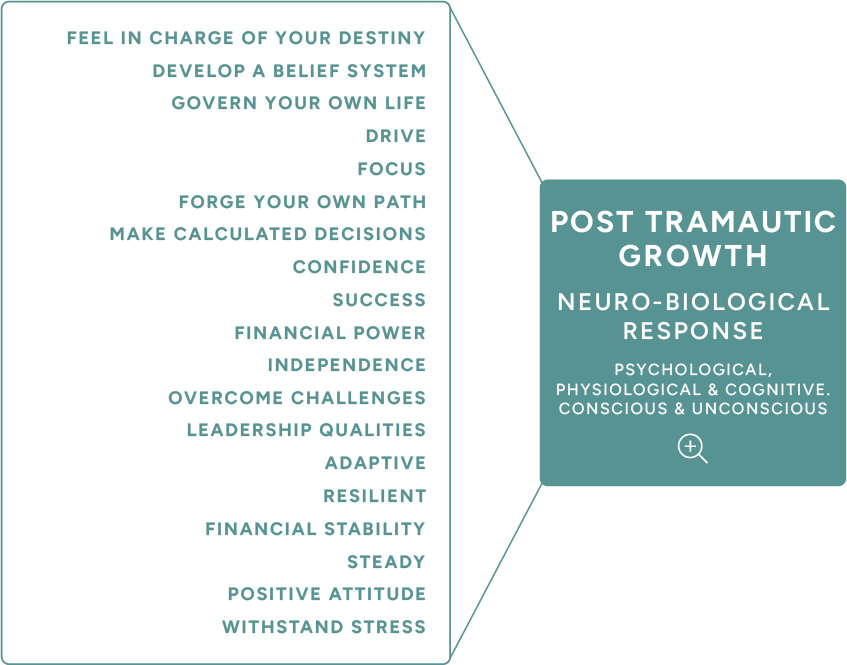

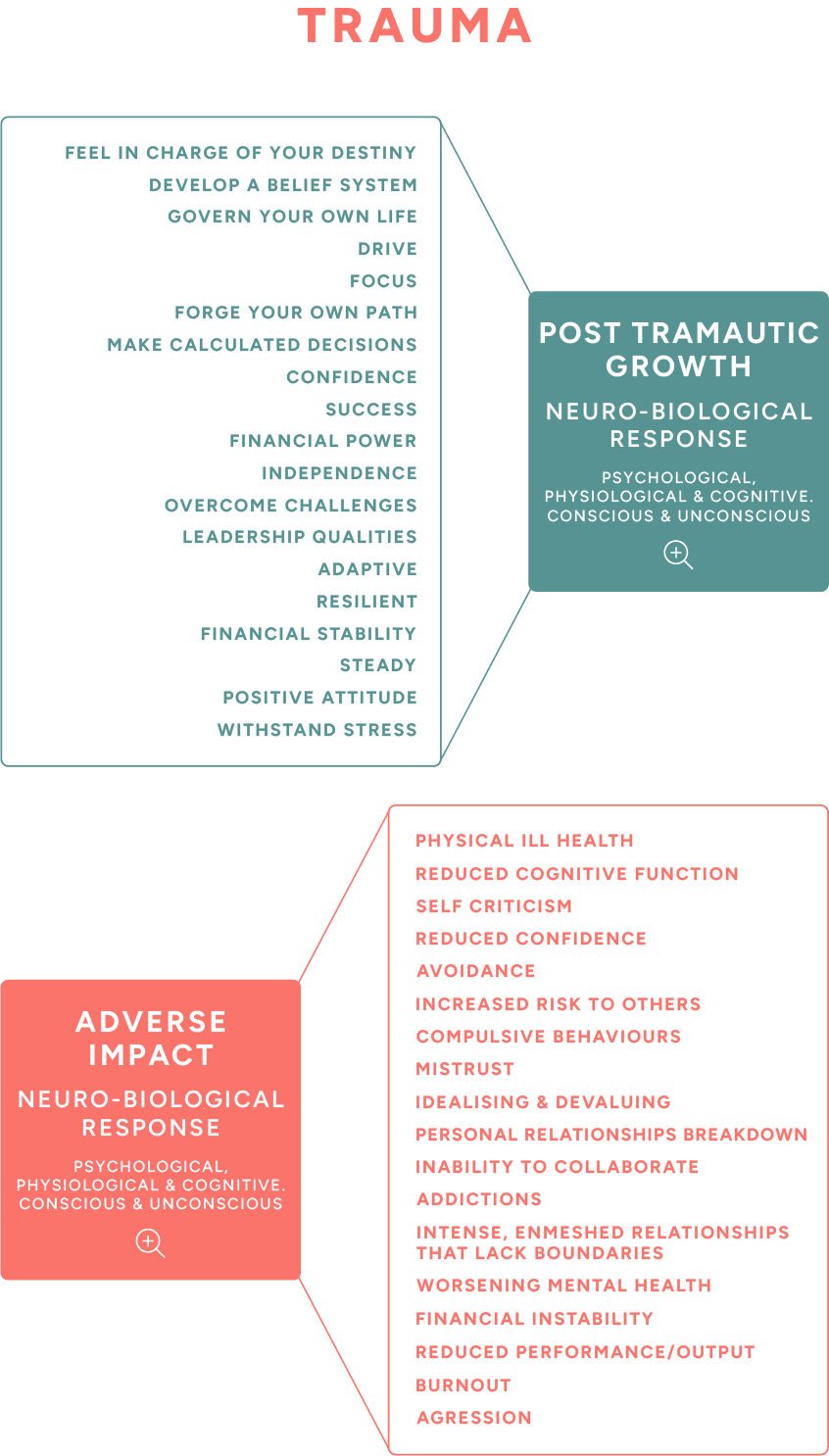

Post-traumatic growth is not simply a psychological construct, it has measurable neurobiological correlates. The “positive neurobiological response” refers to adaptive changes in the brain and body that can emerge after early childhood adverse experiences, allowing us to experience growth rather than being locked in post-traumatic stress.

These adaptive changes develop into coping strategies, sublimating the traumatic memories, beneficial adaptations that often drive us to become high achievers, leaders and elite performers.

We may have clearly defined belief systems, enabling us to build success on thoughts such as:

“One day I will escape this,” “I’ll show you”, “I will be in charge of my own destiny and govern my own life” and “I will never experience this again.” By self-actualising our independence, success and financial power we can become incredibly focused and driven, forging successful careers and attaining powerful roles.

Some of the key positive neurobiological responses include:

Stress system recalibration

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis shows improved regulation compared to chronic dysregulation in PTSD, resulting in healthier cortisol rhythms, supporting resilience, better mood regulation, and energy balance.

Neural plasticity and integration

The hippocampus (memory and contextualisation) and prefrontal cortex (executive control) often strengthen their connectivity, supporting more effective meaning-making, narrative integration of trauma, and emotional regulation. More balanced activity between the amygdala (fear response) and regulatory networks, leads to reduced hyperarousal.

Reward and motivation pathways

Post-traumatic growth is associated with increased dopaminergic activity in the mesolimbic system (ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens), underpinning greater motivation, pursuit of new goals, and heightened appreciation of life.

Oxytocin and social bonding

Positive meaning-making after trauma often co-occurs with strengthened social bonds. Oxytocin release supports trust, empathy, and connection, all of which help consolidate post traumatic growth.

Epigenetic and immune benefits

Trauma can switch on inflammatory gene expression. PTG appears linked to shifts back toward healthier immune function, lower inflammatory markers, and sometimes even beneficial epigenetic changes that buffer against stress.

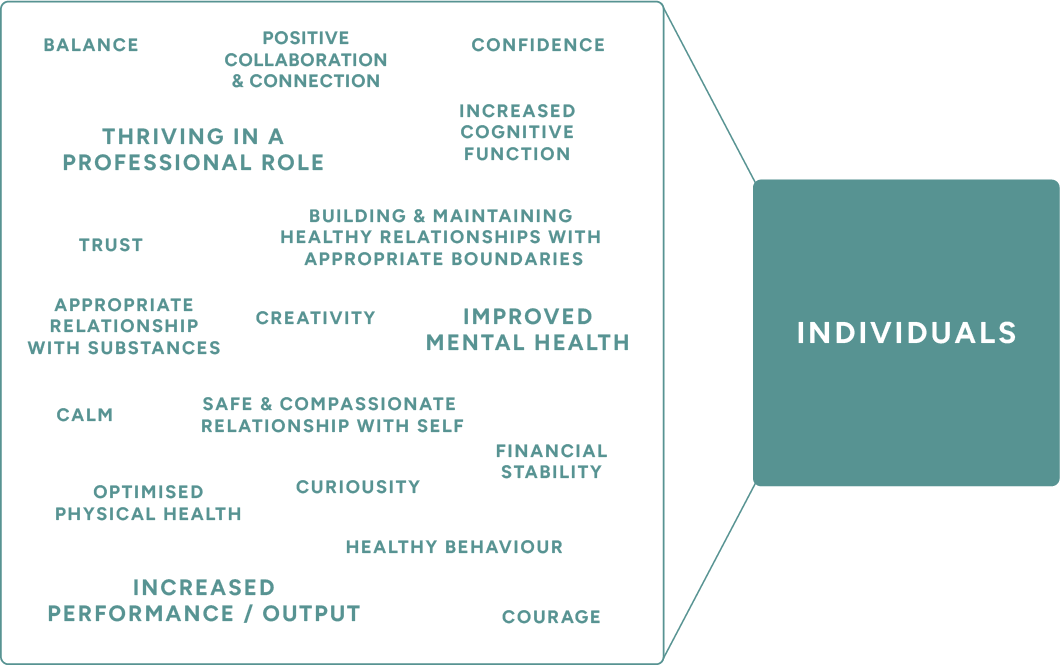

All of this indicates that we have high levels of functionality and are frequently highly positive, adaptable, resilient, with amazing attention detail. Our ability to withstand pressure, our focus, drive and steadiness allow us to navigate change, which benefit the corporate environment where these traits provide a platform to shine, are admired and passed on to others.

To summarise: The positive neurobiological response to PTG is a re-balancing and strengthening of brain networks for regulation, reward, and social connection, along with healthier stress and immune functioning. This “adaptive recalibration” makes the individual not just restored, but often more resilient than before.

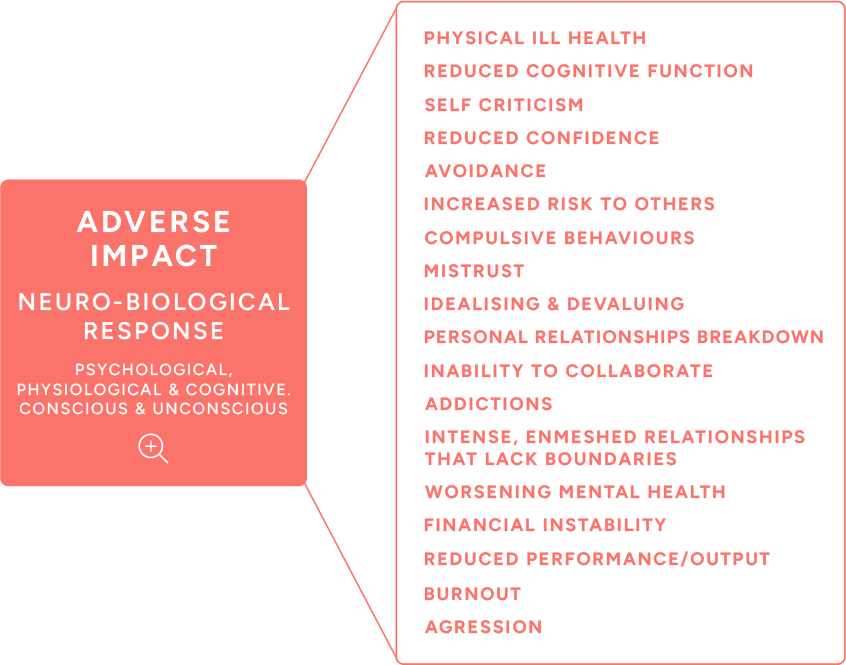

However, it is often assumed that post-traumatic growth is purely beneficial, but neurobiological research suggests there can be adverse or “costly” responses as well. While these traits benefit corporate growth, they are also manifestations of stress, which ultimately can impact our work and relationships.

PTG doesn’t always mean that the nervous system has fully healed; sometimes growth and lingering stress responses coexist. Should our extreme attention to detail and focus result in hypervigilance, we redirect our energy towards increased perceptions of threat, begin to work excessive hours, focus obsessively on immediate results and press our teams and ourselves for increasingly higher standards.

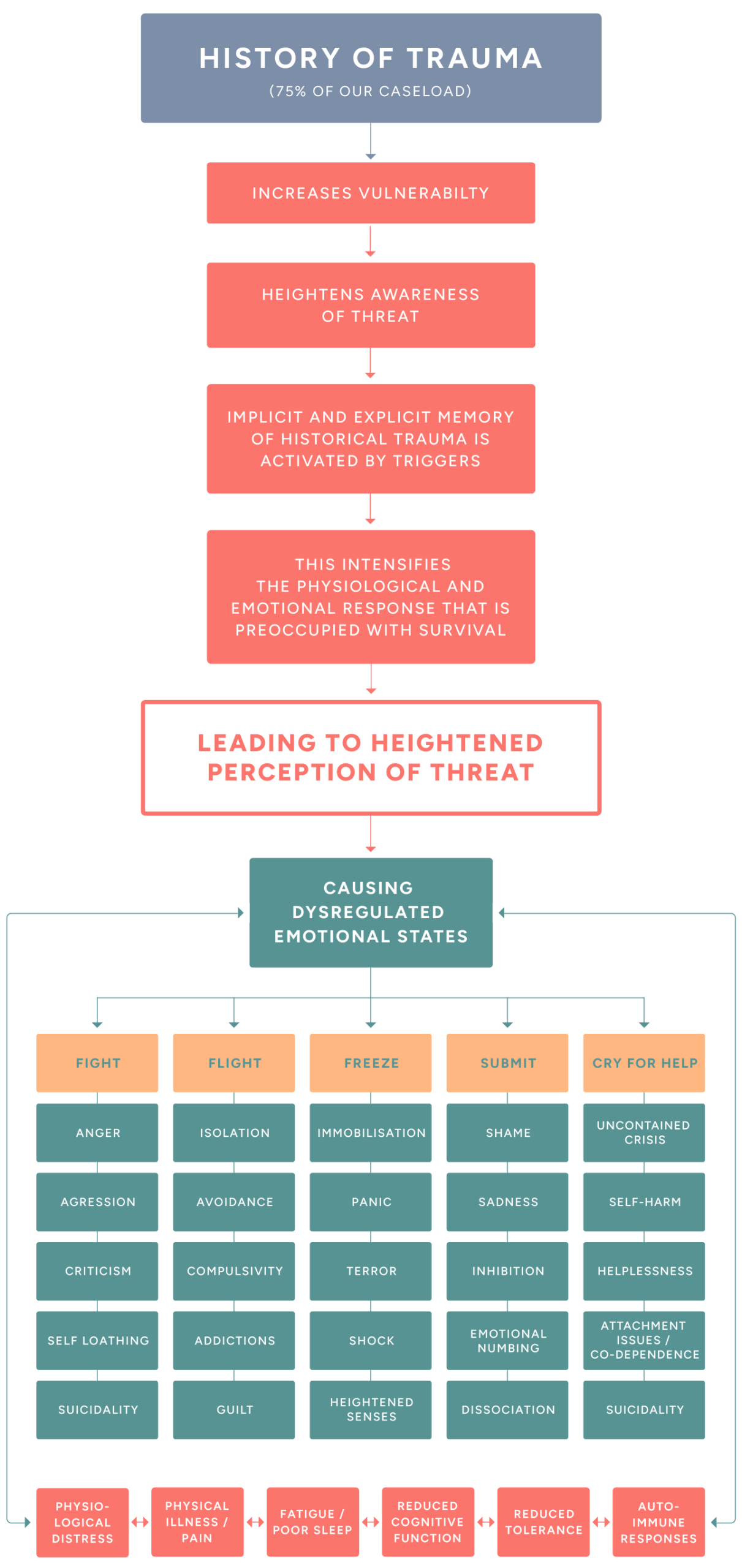

75% of our case load has experienced significant trauma